September 09, 2020

I grew up outside of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in the transition zone between suburban and rural. My grandmother had a stack of old National Geogprahics that I would spend hours leafing through, mostly looking at the pictures. I was fascinated by the incredible diversity of animals depicted on those pages.  I would confidently proclaim, when asked what I wanted to be when I grew up, that I was going to be an explorer. Either that, or a mermaid. Jury’s still out on that one. This is where my love of the natural world was born.

I would confidently proclaim, when asked what I wanted to be when I grew up, that I was going to be an explorer. Either that, or a mermaid. Jury’s still out on that one. This is where my love of the natural world was born.

Mine was a childhood spent outdoors. Exploring the eastern deciduous forest, I remember being interested in all the different types of trees that made up the woods around our house. My dad knew the names of all the different species of trees and he could identify them by their leaves. I thought this was just simply the coolest thing. I was struck by how each type of tree lived in a slightly different type of place and did their “tree-ey thing” in a slightly different way. I didn’t know at the time that I was studying ecology even then.

My fascination with ecology blossomed at college where I majored in biology. I stayed at Penn State for graduate school where I studied how different forestry practices affected the conservation of the endangered Indian bat, Myotis sodalis. I found the work fascinating, but I was frustrated by what I felt to be a disconnect between my explorations and my ability to communicate meaningfully about them. What good did it do for me to know so much about bats, amazing creatures that perform essential ecosystem functions, if most people to whom I spoke thought of bats as pests to be eliminated. This is when I first realized that science had a public relations problem. I decided I wanted to be a part of communicating science and realized that I could do that as a science teacher.

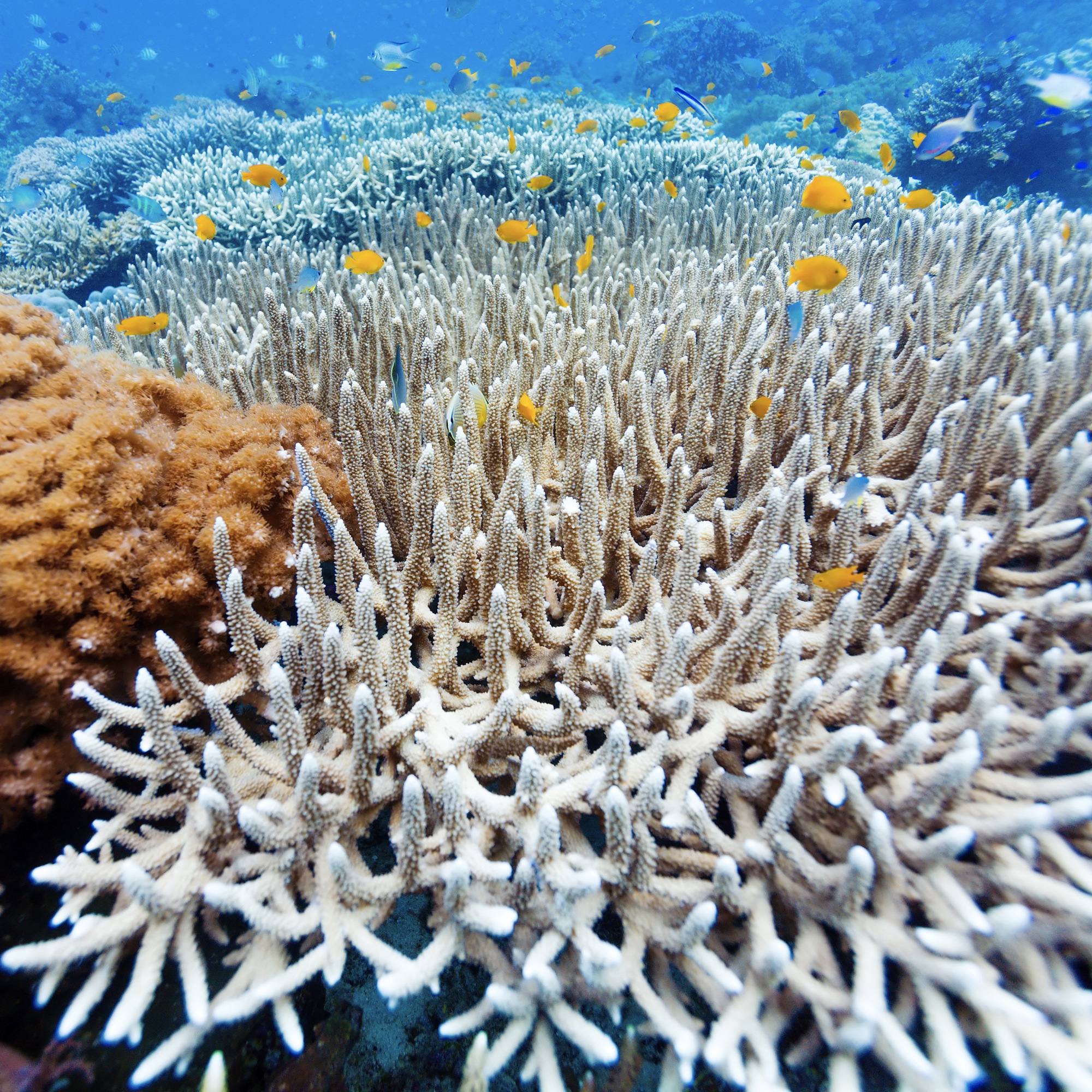

I’ve spent the last twenty years working as a science teacher in both public and independent schools. Most recently, I designed and taught human biology to eighth graders. The goal of this course was to help my students experience science as a process, not a collection of facts, a tool for understanding the world. I sought for my students to understand and appreciate the unity and diversity of life. I hoped that they would develop a love of the natural world and an ethos of stewardship. I always worked to relate our learning to the human experience. It's impossible to teach about the diversity of life and how humanity is a part of it without taking a candid look at human impacts. The library of life is burning. We are experiencing the Anthropocene, the age of humans, and a sixth mass extinction in which the drivers are primarily anthropogenic: global warming, ocean acidification, pollution, habitat destruction. It was essential for me to find a way to teach my students about the challenges facing our natural world but to do so with the “stubborn optimism” exposed by

As I developed my understanding of issues related to global change, I began to become more aware of the plight of our ocean. The ocean is Earth’s life support system. It regulates our climate to make it habitable for life as we know it. Photosynthesis by phytoplankton in the ocean produces 50% of atmospheric oxygen. The ocean is involved in the cycling of many other substances necessary for life and it provides the primary source of protein for a large portion of humanity. In the World is Blue, Dr. Sylvia Earle writes, “With every drop of water you drink, every breath you take, you’re connected to the sea. No matter where on Earth you live.”  This is true for a fledgling scientist studying in the forests of Pennsylvania as well as for a science teacher and her students in Denver, Colorado.

This is true for a fledgling scientist studying in the forests of Pennsylvania as well as for a science teacher and her students in Denver, Colorado.

In the process of learning how to communicate about global change, I was invited by a teaching colleague to work with

So, why the ocean? Why did a terrestrial ecologist turned biology teacher in landlocked Colorado decide to make the ocean the setting of the story of the unity and diversity of life? Because, “No green, no blue. No water, no life.” - Dr. Sylvia Earle. The story of our ocean is the story of all life on this planet. It’s a real page turner and should be required reading.